The search for clean water in Africa often exacts a heavy toll on the lives of women and girls who are responsible for gathering it on a daily basis. In many African countries it takes up to six hours per day to collect sufficient quantities of water to serve a single family, and much of that time is spent walking; the typical round-trip distance is three miles, although in some instances it can be considerably longer. Physically reaching the water can be hazardous, as loose rocks or roots on the paths or at the edge of water sources can cause women to fall and hurt themselves, or in some cases, even die.

The most common vessels for transporting water are Jerry Cans, and when filled with water, they weigh 44 pounds. Carrying this load every day can lead to chronic, significant pain and physical deformities in women’s backs, hips, and necks. Pregnant women are not excused from water collection duties, and the effects of carrying the heavy water often interfere with and complicate childbirth.

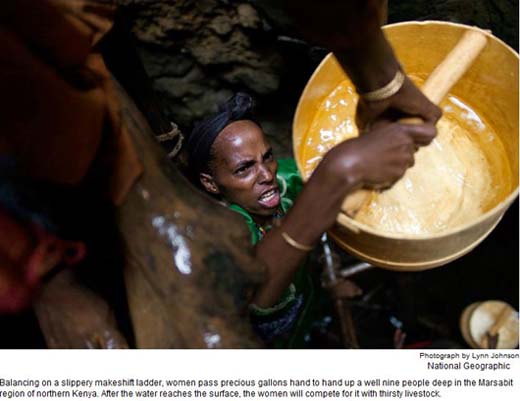

What the women and girls find when they get to the water source—a pond, stream, or hole in the ground—is often less than ideal. They often find scores of other women collecting water from the same location, and the lines are so long that the newly arrived must wait for hours to take their turn.

Women cooking with dirty water unintentionally expose their families to chronic diarrhea, typhoid, cholera, worms, parasites, dysentery, and hepatitis. The leading cause of death in infants is exposure to contaminated water and water-borne diseases. Yet, the water harvested can be dangerous to everyone: 1.8 million people die every year from diarrheal disease, and half of the world’s hospital beds are filled with people of all ages sick from diseases caused by drinking unclean water.

Solving these problems has been the focus of many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international agencies such as the United Nations who have been involved in ongoing efforts to provide clean, potable water to those living in rural and urban areas in developing countries. While varying in their approaches, these actions are collectively improving the daily lives of women and their families.

One of the more widespread technologies used by aid organizations are hand pumps that access water from wells drilled into the ground. Groups such as The Water Project couple the installation of these pumps with community engagement and education classes designed to teach locals about proper hygiene and sanitation practices. Similarly, charity: water and its partners have brought water pumps to clinics and schools in Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia, all of which have dramatically improved the lives of community members.

Solar energy can also play a leading role in providing access to clean water. In areas where there is no power grid and water cannot be accessed by hand or foot pumps because the water table is too deep, the choices for powering deep well water pumps are usually diesel generators or solar systems. The daily output of most village water supply pumps range from 800 to 13,000 gallons per day (3,000-50,000 liters). Fifty-thousand liters is enough to supply 2,500 people with their daily water needs, using UNDP standards of 20 liters per person per day. The effective depth for water pumps to provide this much water is 400 feet (120 meters) or more.

There are very distinct differences between solar and diesel in terms of cost and reliability when it comes to providing reliable and affordable access to water. Diesel powered water pumps are typically characterized by a lower up-front purchase price than a solar system, but they require very high operations and maintenance costs. Diesel gensets typically require regular service—both minor and major—and any required repairs after a breakdown are very costly. In addition, the cost of diesel fuel is prohibitive to the world’s poorest people. Fuel price fluctuates on a daily basis, and over the long-term, it continues to steadily rise.

A solar powered water pumping system usually has a higher up-front purchase price, but it has very low operation and maintenance costs over its lifetime, which is typically 20-25 years. With a solar pump, energy and pumping costs can be accurately calculated for the life of that system, because they have fewer moving parts and require minimal maintenance to keep them running. The only maintenance normally required is cleaning the solar modules every two to four weeks. In addition, they do not require a trained operator on site as do diesel-powered systems.

In the West African country of Benin, many villages in the north suffer from a lack of clean water for drinking and domestic use. To help alleviate this problem, SELF designed and implemented solar power systems to power water pumps for drinking, as well as for irrigation. Up to 8,000 gallons of water are being pumped every day, benefiting approximately 4,500 people living in the communities of Dunkassa and Bessassi. The laborious and time-consuming task of collecting water has been effectively eliminated, and the number of water-related illnesses has dropped.

In addition, water used to irrigate crops during the dry season has resulted in a significant increase in food security and improved nutrition for the communities, who are now able to consume high-value fruits and vegetables year-round.

Access to clean water means better lives for women and girls and their families. Girls no longer have to help their mothers fetch water, and women have more time to work without having to walk to distant water sources or to care for children who are sick from various water-borne illnesses. Women are also able to complete chores faster and have more time to develop marketable skills of their own, or to find work or develop new businesses that will bring in additional income to their households.

And, because water is so often far away from villages, mothers often keep their daughters home from school to help collect water or to care for their younger siblings while they go off to collect it themselves. Giving women access to clean water in the village frees young girls to go to school more often and for longer periods of time.

African women face unique, challenging barriers. Providing them with access to clean water through the use of solar energy can help mitigate systemic disadvantages and introduce new opportunities surrounding health, education, and enterprise.