I’ve just returned from Benin, West Africa where I had a chance to see firsthand the remarkable transformation that has taken place in the villages of Dunkassa and Bessassi since the launching, less than two years ago, of SELF’s solar irrigation project in Kalalé District — a poor, dry region in the northern part of the country.

Kalalé District consists of 44 villages (~100,000 people), none of which are connected to Benin’s electric power grid.

There is precious little rainfall during the six-month dry season that runs from November through April each year. During this period, the land of Kalalé is parched and its people are hungry. Malnutrition is widespread, as evidenced by the many children walking around with distended bellies—a telltale sign of kwashiorkor, a condition caused largely by a lack of protein and micronutrients.

Our involvement in Benin began some three and a half years ago when I was first contacted by Dr. Mamoudou Setamou, a native of Kalalé who had received a Ph.D. in agricultural entomology from the University of Hanover in Germany. Mamoudou, now a Professor at Texas A&M University, had just returned from a home visit to Benin, where he had participated in a meeting of Kalale’s district council to explore alternative options for electrifying Kalalé’s villages since the national grid was not likely to reach this remote part of Benin anytime in the foreseeable future.

Intuiting that solar represented a way forward for his people, Mamoudou turned to SELF for help. After a series of discussions, it became clear that Kalalé District, with its 44 unelectrified villages, offered a great opportunity for SELF to scale its work beyond the scope of a single village to encompass an entire region. After all, with much of Africa still without access to modern energy services, it was time to think and act boldly.

Over the next few months, we put together a plan to generate solar electricity for a wide range of end-uses—including schools, health clinics, water pumping systems, street lighting, and wireless Internet access—in each of the 44 villages that comprise Kalalé District.

In terms of priority, however, an on-the-ground needs assessment revealed that the first concern among the local communities was food security: to find a way to overcome the endemic lack of water and agricultural produce that condemns the people of Kalalé to an endless cycle of poverty and poor health, especially during the 6-month dry season.

To address this problem, we approached Professor Dov Pasternak, a leading drip irrigation expert who, for the past eight years, has been working for the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). While at ICRISAT, Pasternak developed what he refers to as the “Africa Market Garden” – a simple but highly effective method of using drip irrigation to grow high-value fruits and vegetables on small plots of arid land in the Sahel region of Africa.

Prior to working with SELF, Pasternak had relied upon diesel generators to power the water pumps used in his drip irrigation systems. Needless to say, we felt that solar represented a more viable alternative, economically and environmentally. Dov agreed to try it our way, and now with the successful launch of the first solar-powered drip irrigation systems in Benin, he has become a solar convert. (In a white paper SELF recently put together, it is shown that the payback period for solar pumping – as compared with diesel – can be less than two years, and that’s at today’s diesel prices which are going up, and solar prices which are going down.)

My recent trip to Kalalé was the first time I had visited the project since its launching in November 2007. I was accompanied by a French film crew that is going to feature SELF in an upcoming segment of Earth from Above, a National Geographic–like program hosted by well-known French photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand.

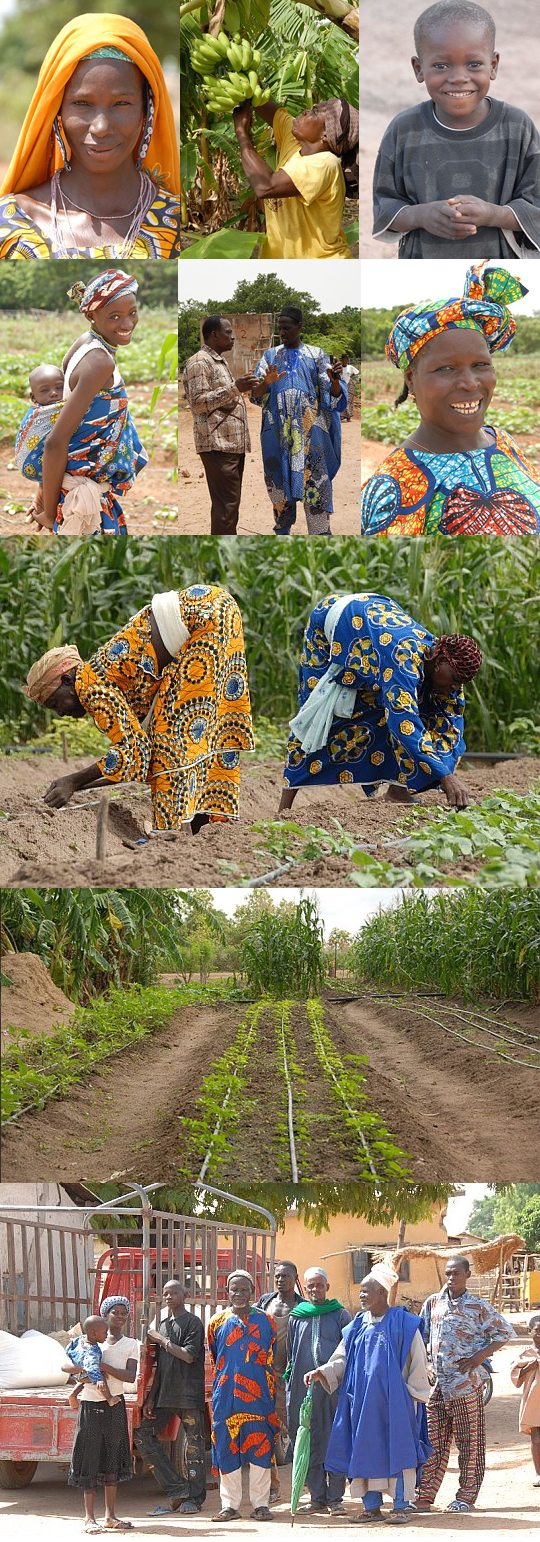

It was great to return to Benin and spend time with the people of Dunkassa and Bessassi, the two pilot villages where solar drip irrigation systems have been installed. I immediately noticed a difference in the women, who looked stronger since our last encounter. Not only are the women better fed, but so are their families and the rest of the villagers who now have year-round access to a steady supply of highly nutritious fruits and vegetables.

What’s more, the women are earning an extra $7.50 per week from the sale of fresh produce at the local market. I was there on market day, and was delighted to see the women march off proudly into town with their baskets filled to the brim with leafy green vegetables.

So not only has nutrition improved in Dunkassa and Bessassi, but income levels also have risen — income which will help pay for school fees, medical treatment, and overall economic development. Indeed, the women are already starting to think about other types of income-generating schemes that can be launched in the villages. It appears their entrepreneurial spirit has been kindled!

Phase II of this project in Benin, scheduled for launch next year, will involve the “whole-village” electrification of Dunkassa and Bessassi, whereby solar electric systems will generate power for the school, health clinic, homes, street lighting, community center, and a WiFi network in each of the pilot villages. We’re also planning to install additional solar pumps that will provide fresh drinking water to the residents of Dunkassa and Bessassi.

While much remains to be done, we’ve gotten off to a promising start in Benin. The tandem use of solar energy and drip irrigation can be replicated in many other parts of sub-Saharan Africa that are poor in water resources but rich in sunlight.

What’s particularly exciting is the fact that in this one project we now have a sustainable model that is simultaneously combating climate change, improving food security, supplying clean water, alleviating poverty, and empowering women.

Stay tuned for further updates…